An Open Letter to Tapas Bar Owners in Sevilla

[para la traducción en español pinchar aquí]

Two years ago I wrote about the increasing number of tapas bars in Sevilla charging for bread and service, a previously unheard of practice that started off in a small way with some bars charging, say 50 cents a basket, but that has now grown to the point where we find a few bars charging up to 2€ PER PERSON.

I’m not singling out any individual bars or restaurants here (I reckon you know who you are) so I’m not going to name names, either to praise or shame. But I do feel it’s time you gave this some thought and tried to understand the damage you are doing, both to the splendid tradition of the tapeo and to your own reputations. Because I actually love some of your bars, and your fab tapas, but enough is enough already.

The main arguments I keep hearing from you and your staff are:

- Everybody else is doing it.

- People pay more in other countries via taxes and tips.

- Why should we give food away?

- You’re the only one who ever complains, Shawn.

First of all, everybody else isn’t doing it. Not even close. The main culprits tend to be the new gastrobars, probably just like yours, especially those located in tourist areas. And hey, why not? By charging every person who walks into your bar an extra euro – for absolutely nothing! – you can probably pay one person’s salary. But let’s be honest here, if you can’t operate at enough of a profit to pay your staff properly then maybe you’re in the wrong business. Charging what amounts to an admission fee is so wrong that I can’t believe it’s been allowed to go on for so long. Yes, we all know that times are tough, but they are just as tough for your customers. Some of you say that many of your customers are tourists so it doesn’t matter, which also says to me that you probably don’t belong in the “hospitality” biz.

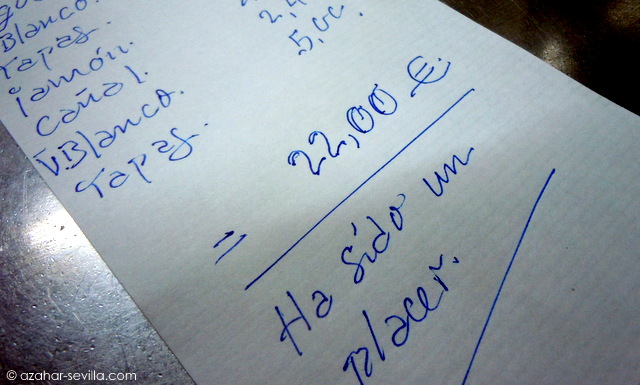

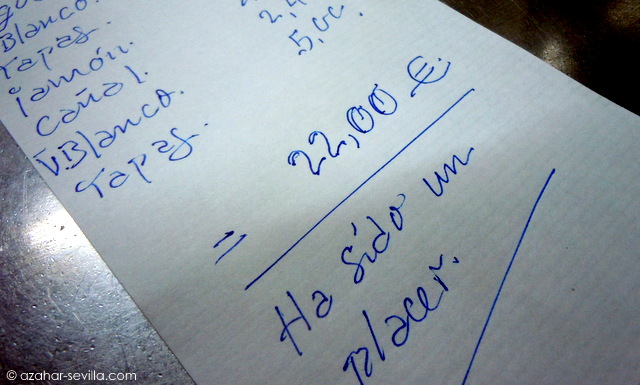

example of a tapas bar that cares about its customers

As for the second argument… what? What has that got to do with anything? We live and work in Spain. As do the majority of your customers. FYI, just a couple of examples here. In the UK the service charge is given to the staff and is not obligatory, and everybody there knows this. In the US and Canada tipping is the norm but is also not obligatory. If you don’t like the food or service, you don’t tip. Simple. But you also get coffee and soft drink refills, baskets of bread/nachos/ muffins, all included in the price. You don’t get charged just for walking into a place and sitting down. Perhaps this happens in other countries, but as already pointed out, we are not other countries. And in this country, especially in Sevilla, el tapeo is a cherished custom that you are threatening to wipe out. Imagine going out with 4-5 of your friends and being charged 1€ per person at every stop… at the end of the evening you will have paid an extra 20-30 euros. For absolutely nothing. So of course people will be forced to stop moving from bar to bar in order to save money, and this very charming element of daily life in Sevilla will die away.

Then there is the mistaken idea that you are somehow giving anything away. Nobody is asking you to give food away for nothing. But when you put food on a table as soon as customers sit down, it later looks very tacky when you charge for it, meaning it makes you look bad. It really does. Since I’ve heard most of you say “Do you have any idea how much bread and olives cost us every month, Shawn?” I’m guessing that you know exactly how much, making this a fixed cost (like rent and electricity) and something that could easily be factored into your food and drink prices. If you feel you want to charge for bread and olives, fair enough. But they should be clearly listed on the menu and you should wait for people to order them.

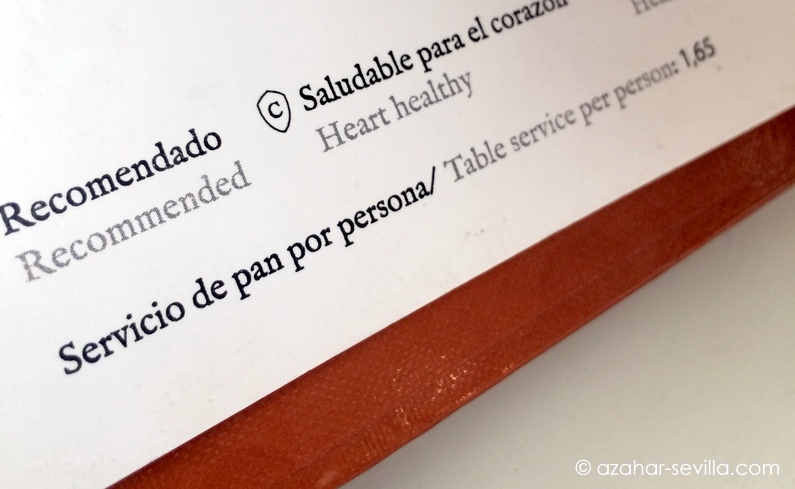

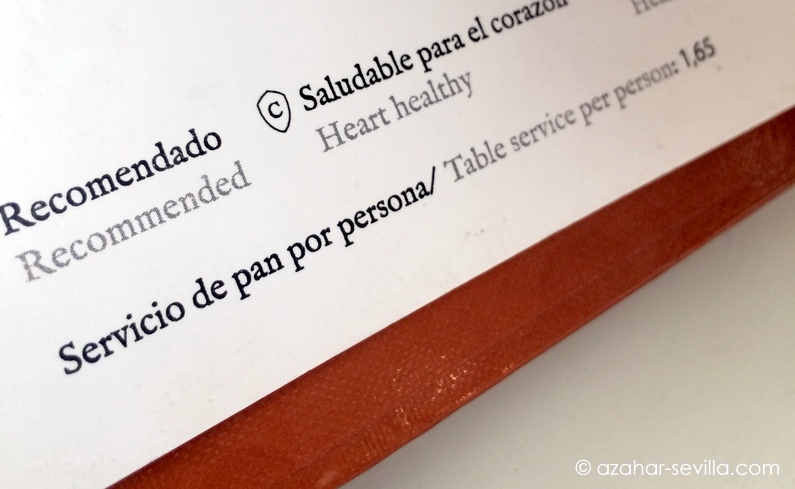

can you believe I was charged 3 euros for THIS

Finally, I am far from the only person complaining about this. I hear complaints all the time, including from other bar and restaurant owners. Heck, even some of your own staff and management are embarrassed by this, but they need their jobs so of course aren’t going to say anything. I am aware that I may be the only one who will say something to your face, but I can’t even begin to count the number of visiting friends and tapas tour clients who have been surprised and put off after finding an extra charge on their bill. I’m often asked if the “service” is a tip that goes to the wait staff. No it is not, I tell them, it goes directly into your pocket. I’m also asked WHY bars in Sevilla do this and my only honest answer is that certain owners have hit on a way to make extra money for nothing and seem to think nobody minds. But people do mind. They mind a lot. Scrupulous bar owners I’ve spoken to also hate this practice and feel it is giving tapas bars in Sevilla a bad name. But do they complain when they go out and this happens to them? No, they do what most people do. Feel upset and taken advantage of and then don’t go back. Why? Because nobody likes making a fuss or getting into an argument at the end of a meal or tapas stop. Easier just to pay up and leave. And you know this.

Sometimes friends have said to me “well, I’m a regular at such-and-such so they don’t charge me”, as if that makes it okay. The truth is that NOBODY has to pay for bread they haven’t ordered, and especially not this atrocious per person service charge. But again, nobody wants to make a fuss. And of course visitors have no idea they aren’t obliged to pay. Even if they did, most don’t have enough Spanish to argue with their server. But it leaves them with a bad feeling after what was an otherwise pleasant experience, which reflects on you.

Not to mention that none of this is in compliance with Official Rules and Obligations which state that bars and restaurants cannot charge for non-food items, specifically cover charges and taking reservations. Nor can they charge for food items that have not been ordered by the customer ie. bread and olives brought to the table.

But legal or not, it is still morally reprehensible to charge people for absolutely nothing. Meaning that if you found that – somehow – it was legal to charge your customers for just taking a seat in your tapas bar… why would you do this to them? What is your excuse or reasoning? And why does a guiri like me care more about preserving the tapeo tradition than you apparently do?

Un abrazo,

Shawn

Continue reading “Death of the Tapeo” →

… and you’re not invited. 😉

… and you’re not invited. 😉

As I sit here writing this a few invitations to meet at the Feria have come in by email or text message. And the other day I was even asked to do a radio interview about Feria (!!) which I turned down for obvious reasons (I don’t think it would have been the interview they were looking for). But you never know. I may end up popping over to people and horse watch for awhile. And before you write me off as a grumpy anti-feriante, I’ve already booked some time off to spend a couple of days at the feria in Jerez, where the casetas are open to everyone and the horses are especially beautiful. Just feels friendlier there somehow.

As I sit here writing this a few invitations to meet at the Feria have come in by email or text message. And the other day I was even asked to do a radio interview about Feria (!!) which I turned down for obvious reasons (I don’t think it would have been the interview they were looking for). But you never know. I may end up popping over to people and horse watch for awhile. And before you write me off as a grumpy anti-feriante, I’ve already booked some time off to spend a couple of days at the feria in Jerez, where the casetas are open to everyone and the horses are especially beautiful. Just feels friendlier there somehow.